What is Variegation?

Variegation refers to a leaf and stem containing more than one colour. It is most commonly associated with plants whose normal foliage colour is green, while their variegated counterparts have areas of yellow or white. Technically, any plant which displays multiple foliage colours is variegated.

The yellow/white commonly seen on ‘variegated‘ plants is actually due to a lack of chlorophyll (green pigment) in some of the plant cells. Chlorophyll is located within the chloroplast (a membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid) and helps the plant absorb light, carbon dioxide and water, and convert it to glucose and oxygen.

There has been a surge in interest in variegated plants over the past decade. Some are sold at garden centres for a few dollars. However, variegated specimens such as Rhaphidophora tetrasperma, Monstera deliciosa and Monstera adansonii sell for hundreds or thousands of dollars.

Origins of the word Variegated

The word variegated is derived from the Latin word variegatus, which is the past participle of variegare. Variegare comes from varius meaning “varied” or “diverse” and ager meaning field or land. Essentially, variegare meant “to diversify” or “to make varied,” in context to the different colours or patterns.

The term variegated was adopted into the English language in the 17th century, and it was used to describe plants that have leaves featuring different colours, usually in the form of blotches, margins, or streaks. Since then, the term has been used more broadly to describe anything that has a variety of different colours or patterns, not just plants.

Pattern gene (natural) variegation

Most of us think of leaves as green, but many plant species have brightly decorated leaves due to different types of pigment. Chlorophyll is the most abundant pigment in the plant kingdom. Carotenoids give plants yellow or yellow-orange hues, while anthocyanins are responsible for red or purple leaves.

This type of variegation is a genetic trait built into the plant’s DNA which programmes different cells to produce different colours and is passed down from generation to generation. There are several advantages to natural variegation, which may act as camouflage or a warning against vertebrate herbivores. Dracaena trifasciata syn. Sansevieria trifasciata (snake plant), Solenostemon scutellarioides syn. Plectranthus scutellarioides (coleus), Calathea spp. and Caladium spp. are examples of plants with natural variegation.

Chimera variegation

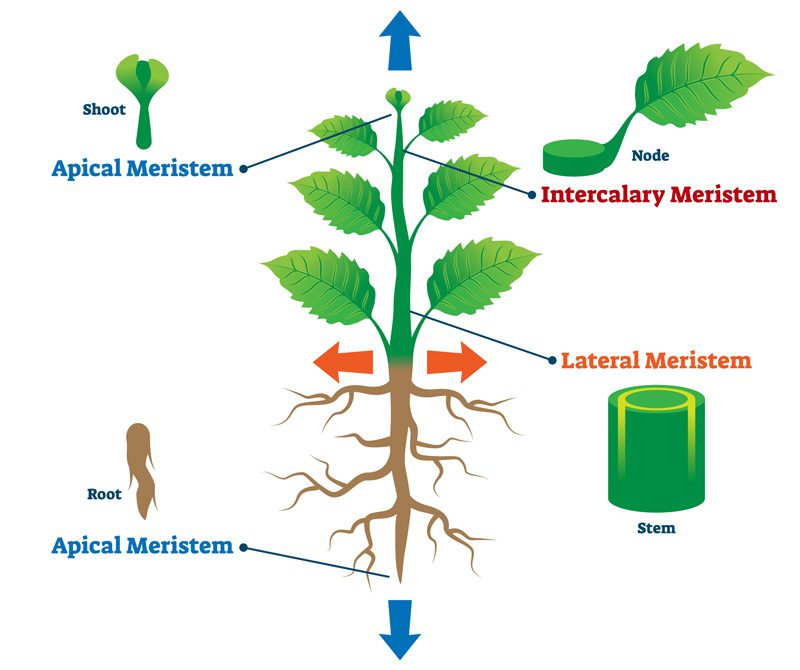

The most common cause of variegation is a genetic mutation in the meristem. This mutation results in a plant with two genotypes, one of which can produce chlorophyll, while the other cell line is unable to.

The meristem is a type of tissue made up of undifferentiated cells that differentiate to form tissues of the plant.

There are three types of chimera variegation: mericlinal, periclinal, and sectorial.

- Periclinal variegation involves the mutation of an entire layer of the meristem which occurs if the mutated cell is located close to the apical dome (a region of cells that are capable of division and growth in the root and shoot tips) so that all divisions create an entire layer of the mutated cell line. Regarded as the most stable of the chimeras, propagation will produce similar growth and patterns to the mother plant.

- Mericlinal variegation is similar to periclinal, but only a portion of the layer is mutated and is classed as unstable. The mutated layer may be maintained in one area of the meristem, producing variegated leaves on that portion only, while other portions of the meristem are non-variegated. The meristem may either remain stable or lose the mutation, reverting to a solid colour.

- Sectorial variegation is due to mutations affecting sections of the apical meristem that extend through all cell layers. Both mutated and normal types can be produced, depending on the point on the apex the shoots differentiate.

Transposon variegation

Transposable elements (TEs) are DNA sequences also known as jumping genes that can change their position within the plant genome through a mechanism called transposition. They were discovered in 1948 by Barbara McClintock in 1948 while working with Indian corn, for which she was later awarded a Nobel Prize.

Interestingly, approximately half the human genome is made up of TEs. We still don’t know the entire impact of these movable DNA sequences, but they can play a role in some diseases and cancers.

TEs can cause changes in gene function and composition, including genetic reprogramming and the creation of novel functional proteins. If the TE inserts into a gene for chloroplast development or chlorophyll production, the resulting tissue will be white.

Blister (reflective) variegation

The outer layer of the non-pigmented epidermis lifts from the pigmented layer below causing an air pocket to form. This creates a transparent patch that reflects light on the leaf surface, giving the leaf a shimmery silver look.

Mosaic virus

Viruses are microscopic infectious entities made up of DNA or RNA and surrounded by a protein coat. They are unable to replicate on their own, instead, they use the cellular machinery inside their host to replicate.

There are over 2000 known viruses that affect plants a host of edible and ornamental plants with an enormous economic impact on the horticulture industry (farmers, garden centres etc) and related business. Mosaic viruses spread from plant to plant via insect vectors (mosquitoes, beetles, thrips), nematodes, fungi, propagation, fomites (inanimate objects such as secateurs) and contact between plants. It can take less than one minute for a plant-feeding insect to acquire the virus.

Some mosaic viruses are host-specific and cannot infect different species of plants and are named after their hosts. For example, tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), watermelon mosaic virus (WMV) etc. Other mosaic viruses have a wide range of hosts.

Infected plants can display a range of clinical signs including stunted growth, leaf curling, green and yellow mottled or marbled pattern on the foliage which gives a variegated appearance. One of the most well-known mosaic viruses in the flower world is the tulip-breaking virus (also known as the tulip mosaic virus). TBV leaves an attractive striped pattern on the flowers and was responsible for ‘tulipomania‘ in the seventeenth century and striped tulips were highly sought after. Unfortunately, TBV also weakens the plant and the striped tulip almost died out, with only a small number of varieties remaining. However, due to the devastation the virus causes to commercial tulip crops, it is illegal to grow TBV-infected plants without a license.

There is no cure for the mosaic virus and affected plants should be destroyed. This is one case where variegation is not a good thing.

Caring for a Variegated Plant

Variegated plants can be a little more difficult to grow than their non-variegated counterparts. As some variegated plants can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, my first recommendation is to become familiar with non-variegated plants before you move on to their variegated cousins.

Because variegated plants have less chlorophyll in their leaves, they are slower growing. For this reason, variegated plants need more light to enable them to photosynthesise effectively. Having said that, more light can also burn leaves, so it can be a bit of a balancing act. If natural light is an issue, invest in a good-quality grow lamp.

I like to let new plants settle in for a week or two before I repot them. Always select a premium potting mix, and use an appropriate-sized pot for the plant. A tiny plant with a 2.5 cm root ball does not need to go into a 30 cm pot, but a plant with a 30 cm root ball should be given a pot large enough for it to grow into.

Feed the plant with good-quality fertiliser during the active growing season. You may also choose to supplement these feedings with a plant tonic (I use Powerfeed by Seasol) which can improve soil structure, promote growth and enhance colour.

Common Variegation Terms

The following examples are words most commonly used to describe yellow, cream or white variegation and not the colourful variegation on plants such as coleus. These terms can help plant collectors understand exactly what they’re getting.

Half-moon: The leaf or leaves are made up of half white and half green

Half moon variegation.

Half moon variegation.

High variegation: The leaf or leaves contain a large amount of white or cream variegation

High variegation.

High variegation.

Low variegation: The leaf or leaves contain a small amount of white or cream variegation

Low variegation.

Low variegation.

Suicide leaf: An all-white or yellow leaf

All white leaf on a Monstera deliciosa var. borsigiana albo-variegata alba.

All white leaf on a Monstera deliciosa var. borsigiana albo-variegata alba.

Blocky: When a variegated plant has a block of white (or yellow) on the leaf, this solid pattern is highly sought-after

Blocky variegation.

Blocky variegation.

Marbled: Evenly distributed patches of white or yellow and green across the leaves

Marbled variegation.

Marbled variegation.

Sectoral: A part of the leaf has a solid white, cream or yellow variegation

Sectoral variegation.

Sectoral variegation.

Variegation colours

- Sport or mint: Light green variegation

- Albo: White or cream variegation

- Aurea: Yellow variegation

Frequently Asked Questions

What should I do if a leaf on a variegated plant grows out all green?

Sometimes a new leaf will grow out green, this is known as reverting. To prevent the entire plant from reverting to green, snip off the new all-green leaf.

What should I do if a leaf on a variegated plant grows out all white or yellow?

While an all-white or yellow plant is dazzling, its lack of chlorophyll means it won’t survive. Plant enthusiasts refer to these leaves as ‘suicide leaves’.

The leaves above came from my variegated Rhaphidophora tetrasperma. The axillary bud developed along a highly variegated portion of the node, resulting in all-white leaves. I waited until the third leaf had emerged in the hope some green may develop, but as this didn’t happen, I sadly removed the newly developed leaves as they are non-viable. I would rather the plant put its energy into healthy stems and nodes.

Why are variegated plants so rare?

Not all variegated plants are rare (or expensive). Variegated Schefflera arboricola (umbrella tree) and Hedera helix ‘Variegata’ (English ivy) and Ficus pumila variegated (creeping fig) are common varieties of variegated plants that sell for only a few dollars. Our local Aldi is currently selling Ficus elastica ‘tineke’ for $10.00.

The price is determined by the availability of the plant. As the number of available variegated Monstera deliciosa spp., has increased, the price has slowly started to drop. However, plant collectors can still expect to pay several hundred for a small specimen.

The most expensive variegated plant I have seen on the market was a Philodendron ilsemanii variegata, with a price tag of AUD 14,000 and in June 2021. A R. tetrasperma (mini monstera) sold for over $20,000. This is just how much collectors are willing to pay for a rare variegated specimen.

Why are variegated plants so expensive?

Most variegated plants can only be propagated from stem cuttings, leaf or seeds will not be true to type (ie; variegated). All commercially sold Monstera deliciosa ‘Thai Constellation’ come from tissue culture from a single laboratory in Thailand. With only one global supplier and high demand, this makes for an expensive plant.

Plant collectors do make their cuttings from variegated plants, often to raise funds to add new plants to their collection. Cuttings may be rooted or freshly cut. Inexperienced plant collectors should always purchase rooted and established plants.

Why do some variegated plants revert?

Naturally, variegated plants such as coleus won’t revert, because the colour/pattern is written into the plant DNA. Chimeric plants can and do revert, especially unstable mericlinal and sectorial variegated plants. Aside from natural variegation, most variegated plants can potentially revert to all green. There are several causes of this, including extreme heat or cold, as well as low light levels where the plant’s natural survival mechanism kicks in and reverts to its original state (all green).

Where can I buy a variegated plant?

Common variegated plants are readily available at most garden centres or online plant retailers. From time to time they may also sell rarer specimens, usually Monstera deliciosa ‘Thai constellation’. Rare variegated plants are usually sold privately on Facebook groups, Facebook Marketplace and Etsy.

Propagating variegated plants

Propagating is easy, but care must be taken when selecting a node with an axillary bud. Look for a bud that has formed over a variegated node.

The cuttings below were also removed from my variegated Rhaphidophora tetrasperma while I was removing the white leaves. The image on the left is an axillary bud, which is the precursor for a new shoot. As you can see, has developed over an area with no variegation. If the bud is activated, the resulting growth would be all green. However, had the bud formed over the variegated portion of the node in the right-hand image, the new growth would have been variegated.

Buying rare variegated plants online

The Internet has made sourcing rare and unusual plants considerably easier for collectors, but it is not without its risks. The popularity of rare plants, and the high price tag can, unfortunately, attract scammers.

- Where possible, purchase plants from a reputable nursery.

- Do your research so you have a good idea of the value of the plant(s) you’re looking for.

- Sellers will often include a photo of the mother plant the cutting came from. This is to show what the baby can be expected to look like. However, be aware that the mother plant is not the plant you will receive. This is not a scam as such, just be aware that the mother plant is not the plant you will receive.

- Where possible, pick up and pay for the plant in person.

- If you’re buying a plant via social media, check out the seller’s profile. Does it look legitimate? How long have they had their account? Are they on any groups you’re also a member of?

- Know what the plant you’re looking for looks like. If you’re looking for an M. deliciosa ‘Thai constellation‘, do you know what they look like?

- Unless you have experience propagating plants, always look for a well-rooted plant. Often people will sell a cutting that has only just begun to produce roots. There’s nothing wrong with this, but leave those to more experienced plant collectors.

- Do a reverse image search of photos in listings. Save a copy of the image in the advertisement, go to tineye.com, and upload the photo. Is it a stock photo? For example, all the images in this article are stock photos. There are several causes of this, including extreme heat or cold, as well as low light levels where the plant’s natural survival mechanism kicks in and reverts to its original state (all green)., but I have purchased the rights to use them. A scammer can easily obtain stock images and try to pass them off as a plant they’re selling.

- Check the location of the seller. Are they in the same country as you? If they’re not, does your country have restrictions on importing plants? You do not want to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on a plant only to have customs seize and destroy it. I only purchase plants within Australia, which is where I am located.

Julia is a writer and landscape consultant from Wollongong with a love of horticulture. She had been an avid gardener for over 30 years, collects rare variegated plants and is a home orchardist. Julia is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge of plant propagation and plant toxicology. Whether it’s giving advice on landscape projects or sharing tips on growing, Julia enjoys helping people make their gardens flourish.