As an avid citrus grower with over twenty citrus trees in my garden, I have found citrus to be one of the easiest and most rewarding fruit trees to grow. Citrus is one of the most diverse species of fruiting tree, from the tart ‘acid citrus’ to the sweet and juicy oranges and dekopons. Not only does freshly picked citrus taste great, it also has ornamental value in the garden and the flowers produce a beautiful sweet scent.

The shape of the flower is ‘actinomorphic‘, which refers to its radially symmetrical shape. The peak blooming time is spring, but some types of citrus in temperate zones produce flowers and fruit year-round.

Most of us think of citrus as a Mediterranean fruit as it is widely cultivated there, however, it is not native to the region. Citrus originated in Asia. Bitter oranges (Citrus aurantium) were first brought to Europe by the Arabs, who had acquired them from Asia. They were probably introduced to Spain and Sicily sometime between the 10th and 12th centuries during the period of Arab rule.

Sweet oranges (Citrus × sinensis) are the most abundant citrus fruit in the world, and make up approximately 40% of all imports. Oranges are widely consumed raw, or juiced. China, Brazil, and the United States are the top producers of sweet oranges. dIn Japan, the yuzu (Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka) and sudachi (Citrus sudachi Hort. ex Shirai) are popular varieties of citrus but are not widely cultivated in the Western world.

What type of fruit is citrus?

Citrus fruits are classed as hesperidium. Hesperidium is a type of modified berry that is made up of a tough, leathery rind, which protects the delicate pulp inside.

The outside of a citrus fruit consists of a thick, aromatic rind (exocarp and mesocarp), commonly known as the zest and peel. Beneath the rind is a white pith (albedo), and below that, the juicy segments (endocarp) which contain the seeds. The segments are filled with juice vesicles, which are specialised hair cells.

One of the distinctive features of hesperidium is its way of storing citric acid, which is stored in vacuoles of the juice vesicles, giving the fruit its characteristic tart flavour.

Dwarf vs full size

Dwarf citrus trees are great for decks, patios or small gardens. They typically grow to a height of 1.5 metres (5 foot), which makes it easy to harvest the fruit. The volume of fruit on dwarf citrus is generally the same as the full-sized counterpart.

Rootstock is responsible for the ultimate size of the tree. Dwarf trees are grafted onto rootstock to encourage dwarf growth habits. One of the most common dwarf rootstocks is a mutation of Citrus trifoliata, known as C. Trifoliata ‘Flying dragon’. This deciduous citrus relative is popular due to its hardiness and ability to induce dwarfing in the grafted tree.

Dwarf trees are easier to manage than their full-size counterparts and are more suitable for small gardens or container gardening. Full-size trees have a longer lifespan (50 years vs 25 years) and produce a higher fruit yield.

Both full-size and dwarf citrus are suitable for pots. As the pot will restrict root growth, a full-sized citrus will not grow as tall as it would in the ground.

Why are citrus trees grafted onto rootstock?

Grafting involves combining a rootstock with a scion. The scion is a cutting from a citrus tree with desirable traits, with the rootstock, which is a young tree with a robust root system, disease resistant and hardy to certain temperatures. The scion is secured to the rootstock so that their cambium layers align. This allows the scion to inherit the favourable traits of the rootstock, and ensure the citrus only produces the desired fruit.

- Quick propagation of desired variety: Grafting allows for the reproduction of the exact genetic copy of a desired citrus variety, ensuring that the fruit’s quality and characteristics are preserved. Growing trees from seed is slower, and as many citrus trees are hybrids, there is no guarantee the seedling will have the same characteristics as the parent plant.

- Disease resistance: Many citrus rootstocks have been selected for their resistance to certain pests and diseases, such as citrus tristeza virus, phytophthora root rot, and root nematodes. Grafting onto these rootstocks can help protect the scion (the upper part of the graft that will become the fruiting part of the tree) from these threats.

- Improved tolerance to soil and climate conditions: Some rootstocks are more tolerant of certain soil types, pH levels, salinity, or climatic conditions than others. Choosing the appropriate rootstock can improve the success and productivity of the tree, even when grown in less-than-ideal conditions, such as areas with frost.

- Control of tree size: Rootstocks influence the size of the mature tree, resulting in dwarf varieties that are easier to harvest and suitable for small areas.

- Tree longevity: Some rootstocks can enhance the lifespan of the citrus tree, resulting in more productive years.

Common citrus rootstocks

Citrange (Citrus sinesis x Poncirus trifoliata) a hybrid that performs well in clay loams. Popular cultivars include ‘Troyer’ and ‘Carrizo’. Sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) grows well in sandy to medium loam soils but is less tolerant of heavy, wet soils, nematodes and root rot. Other pros include good fruit quality and vigorous growth.

Hardy orange (Poncirus trifoliata) is valued for its cold hardiness, resistance to various diseases including citrus tristeza virus and nematodes, and its ability to adapt to a variety of soil conditions. Poncirus trifoliata ‘Flying dragon’ provides the advantages of standard trifoliate orange rootstock, such as cold hardiness and disease resistance, while also inducing dwarfing in the scion, which makes it ideal for smaller spaces or container growing.

Sour orange (Citrus aurantium) is only suitable for lemons and limes. This rootstock produces high-quality fruit, thrives in a wide range of soils and has tolerance to root fungi, nematodes, and cold.

Are multi grafted trees recommended?

Also known as fruit salad trees, multi-grafted trees contain more than one species of citrus. For example, you may have lemon and lime, or grapefruit and orange. You cannot have different genera, such as an apple and an orange grafted tree.

The idea of multi-grafted sounds great, especially if space is an issue. You will often find that one of the grafts will take over the whole tree. I’ve had two grafted citrus, one was orange, lemon and grapefruit, and the other was lemon and lime. The orange, lemon and grapefruit became an orange tree, and the lemon and lime is almost all lime, with one small branch that gives me 1 – 3 lemons a year. The lime portion produces around 100 times a year.

Pot vs ground

Both dwarf and full-size citrus trees are suitable to grow in the ground or in large pots. People renting may choose to grow citrus in a pot so they can take it with them when they move. Potted citrus is also great for small gardens or decks. Some varieties of citrus such as kumquat and calamondin have ornamental value. I have three potted calamondins on my deck purely for their visual appeal. Calamondin isn’t a fruit I would normally eat (I will probably try my hand at a calamondincello this year), however, they make great ornamental citrus because they flower and fruit almost year around.

Bear in mind that fruit yield will be greatly reduced if the tree is grown in a pot. A mature citrus can produce up to 200 fruits in a season, compared to a pot-grown one which will only produce twenty. The productivity of a lemon tree is also influenced by factors such as proper pruning, adequate sunlight, appropriate fertilisation, sufficient water, and disease control. Providing optimal care and maintaining the tree’s health can help maximise its fruit production.

What is the best pot to grow citrus in?

The pot should be at least 40 cm (16 inches) in diameter and ideally as wide at the top as it is at the bottom. Egg-shaped or standard pots are ideal for your citrus. My preference is egg-shaped pots as they are more stable than traditional pots that tend to be much narrower at the bottom. Potted, citrus trees, especially when laden with large fruit such as grapefruits or oranges can be top-heavy and prone to toppling over in pots that are too narrow at the bottom.

Terracotta not only looks great, but the porous nature of terracotta can help to regulate moisture levels in the soil. The pot can absorb excess water when the soil is too wet and then slowly release it back into the soil as it dries out.

When is the best time to plant citrus?

Spring is the best time to plant your citrus tree as the soil is warming up. This gives the tree a full growing season to establish itself before the colder weather sets in. If you’re growing the tree in a pot indoors or in a greenhouse, the planting time isn’t as critical, but again, spring is often the best choice.

Are citrus self-pollinating?

Almost all varieties are self-pollinating (also known as self-fruitful). A self-pollinating citrus can produce fruit without the need for another citrus to cross-pollinate. Citrus trees can also cross-pollinate with other citrus varieties, resulting in hybrid varieties. The fruit will remain the same, but the seeds within the fruit will be hybrid.

Even self-pollinating trees can benefit from cross-pollination, which can help to increase fruit set and yield. Gardeners may choose to cross-pollinate by hand or attract pollinators to the garden by growing a variety of flowers.

Bees and other pollinators play a crucial role in both self-pollination and cross-pollination by transferring pollen from the male parts of the flower to the female parts. Thus, while citrus trees don’t need another tree to bear fruit, they often do need pollinators.

How to choose a citrus tree

Look for healthy trees with fresh, mature green leaves and no evidence of damage to the leaves or stem. Fruit on a citrus tree is not an advantage, as it should be removed for the first 2-3 years to allow the citrus to put its energy into growth and not fruit production.

How to care for a citrus tree

As an avid fruit grower, I find citrus one of the easiest and most rewarding fruits to grow. I personally love the more tart varieties such as lemon, lime, grapefruit and finger lime.

Soil

Citrus trees grow best in soil that is aerated, well-drained, and sandy loams. If growing in the ground, clear the site of plants and plant roots as the citrus root system is concentrated in the top 30-50 cm of soil and it doesn’t like competition around the root ball.

Well-drained and aerated soil is vital for citrus trees to avoid root rot. Citrus trees do not grow well in heavy clay soils unless aeration, drainage or mounding is provided.

Optimal pH range

Citrus prefers slightly acidic to neutral pH between 6.0 and 7.5. Within this range, citrus trees can efficiently absorb essential nutrients from the soil. Soil that is too acidic (below 6.0) can result in nutrient deficiencies as acidic soil hinders the availability of essential nutrients such as phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium, leading to stunted growth and yellowing leaves. Soil pH that is too high, (above 7) can result in citrus trees that struggle to absorb zinc, iron and manganese, which can cause yellowing leaves with green veins.

Testing soil pH test is important to determine the pH level of the soil to ensure that the soil provides optimal conditions for their growth, nutrient uptake, and overall health.. Soil testing kits are readily available at garden centres or online. A pH kit will provide you with accurate information on your soil’s pH which will enable you to make adjustments. To lower alkaline soil, add sulfur, peat moss, or organic matter with high acidity. To raise the pH in acidic soil, apply lime or other alkaline materials.

Soil type

Citrus trees thrive in loamy or sandy loam soil, which provides a balance between good drainage and water retention. Avoid heavy clay soils that can hold excess moisture and lead to root rot. Incorporating organic matter into the soil improves its structure, drainage, and nutrient-holding capacity. Compost, well-rotted manure, or leaf mould can be added to enrich the soil before planting citrus trees.

Adequate drainage is crucial for citrus trees. Excessive moisture can lead to root rot as the soil becomes compacted, removing air pockets that are critical for the roots to obtain enough oxygen. If your soil has poor drainage, amend it with organic matter or create raised beds to improve drainage.

Nutrients

Citrus trees require a good balance of essential nutrients for healthy growth and fruit production. Conduct a soil test to determine nutrient deficiencies and amend the soil accordingly.

Nutrient |

Functions |

Deficiency Symptoms |

Excess Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N) | Nitrogen is crucial macronutrient necessary for the manufacturing of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins that are necessary for the development of cellular structures and plant enzymes that facilitate biochemical reactions. It also plays a significant role in chlorophyll production that enables plants to convert sunlight into energy via photosynthesis. As part of the DNA and RNA structures, nitrogen is essential for cell division and growth, influencing the overall growth rate of the plant, leaf development, and seed and fruit production. |

Yellowing or pale green leaves (chlorosis), and stunted growth. |

Excessive vegetative growth at the expense of flowering and fruiting. May also make thick fruit rinds, delayed maturity of fruit and lowered juice content. |

| Phosphorus (P) | Phosphorous is a vital part of the ATP (adenosine triphosphate) molecule, which provides energy for many processes in the plant, including growth and reproduction. It is also necessary for the formation of DNA and RNA, which carry genetic information for new cell growth. Phosphorous contributes significantly to root development which enhances nutrient and water uptake and is also involved in flowering and fruiting, and seed development. |

Stunted growth, delayed maturity, reduced yield, and dark, sometimes purple, foliage. Puffy fruit, bumpy rinds and open centre cores. |

Interferes with micronutrient uptake (iron, zinc, manganese, leading to deficiencies of these nutrients. |

| Potassium (K) |

Potassium is involved in water regulation within the plant cells, helping to control the opening and closing of stomata, which, in turn, affects water usage and photosynthesis. As a vital component in protein and carbohydrate synthesis, potassium is essential for overall plant growth, development, and health. It is also key to the activation of many enzymes, strengthening plant cell walls and contributing to stronger, more disease-resistant plants. Potassium aids in the translocation of sugars, effectively distributing energy throughout the plant, which is particularly important for fruit and seed development.

|

Older leaves turn yellow at the edges and between veins, weak stems. |

High potassium can interfere with the uptake of other nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, and nitrogen. |

| Magnesium (Mg) | Central atom in chlorophyll, essential for photosynthesis. magnesium activates many of the enzymes involved in cell growth and reproduction, contributing to the successful progression of seed development. Magnesium is also essential for the creation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the main energy carrier in all living organisms, necessary for the energy-intensive process of seed formation and maturation. |

Intervenal yellowing (yellowing of leaves between veins), beginning with older leaves. | Rare, but may lead to calcium deficiency. |

| Zinc (Zn) |

Zinc is a crucial micronutrient in plants, that is a vital

component in many enzymes and proteins and is involved in the synthesis of auxins, a type of plant hormone instrumental in regulating growth. It aids in the formation of chlorophyll and some carbohydrates, and assists in starch formation and protein synthesis, all of which contribute to the overall growth and development of the plant.

|

Stunted growth, reduced leaf size, and interveinal chlorosis, a condition where leaf tissue turns yellow while the veins remain green. In severe cases, deficiency can also lead to necrotic spots or distorted leaves. |

Excess is rare but can be toxic to plants, potentially inhibiting plant growth and development, and causing leaf discolouration, root damage, and reduced crop yield. |

| Manganese (Mn) | A vital micronutrient for plants, that is a necessary cofactor in enzymes involved in photosynthesis, respiration, and nitrogen metabolism. Manganese aids in the formation of chloroplasts and is crucial for the process of photosynthesis, facilitating the conversion of light energy into chemical energy. |

Interveinal chlorosis in younger leaves and necrotic spots. |

Leaf discolouration or necrosis, root damage, and inhibited growth. In alkaline soils, manganese may become unavailable to plants, causing deficiency symptoms even when manganese levels are adequate. |

| Iron (Fe) | Iron is a component of many proteins and enzymes involved in photosynthesis, respiration, and nitrogen fixation. It is a key constituent of proteins involved in electron transport, facilitating energy production and is also integral to chlorophyll synthesis, although it’s not part of the chlorophyll molecule itself. |

Yellowing between the leaf veins while the veins themselves remain green, most noticeably in young leaves. This occurs because iron is necessary for the formation of chlorophyll, which gives leaves their green colour. |

Seldom identified but can cause bronzing or tiny brown spots on leaves, ultimately inhibiting plant growth. |

A commonly recommended ratio for citrus trees is 2:1:1 or 3:1:1 of N:P:K. So, for example, a citrus fertiliser might have an N:P:K ratio of 6-3-3 or 9-3-3.

Blood and bone contain nitrogen and phosphorous, to make it complete, add a quarter of a cup of sulphate of potash per kilo of blood and bone. Add fertiliser to moist soil in a band around the tree, starting at the drip line (outer edge of the tree), and work inwards, halfway towards the trunk. Rake, mulch, and water immediately afterwards.

Soil moisture:

Citrus trees require consistent moisture, but the soil should never be waterlogged. The goal is to keep the soil evenly moist. A deep watering every 7 to 10 days (depending on the weather and soil type) is typically sufficient for mature trees, while younger trees usually require more frequent watering. It’s important to water deeply to encourage the development of a robust root system that can access water lower in the soil.

Overwatering can lead to root rot. When the soil is waterlogged, the spaces between soil particles become filled with water, starving the roots of oxygen. Overwatering can also promote the growth of various fungi and bacteria that cause root rot. These pathogens are present in the soil in small quantities without causing problems. However, in the anaerobic (low-oxygen) conditions created by overwatering, they can multiply rapidly and start attacking the weakened roots.

Water

Although citrus are somewhat drought-tolerant, they prefer a consistent water supply to thrive. Water deeply and thoroughly, to ensure the water reaches the deeper roots. Deep watering encourages a robust root system, critical for the overall health and stability of the tree. Water in-ground citrus once a week, or twice a week for potted citrus during the drier months and less often in autumn and winter.

Sunlight

Citrus trees grow best in an open position where they receive a minimum of five hours of full sun each day during the growing season. Sun is necessary for growth as well as the accumulation of sugars in the fruit.

Harvesting citrus

Harvest your citrus when it has reached its colour. Most citrus fruits are ready to harvest from winter to spring, and they should easily be removed from the tree when it is ready. Fruit left on the tree for too long will eventually lose its flavour and become dry.

Citrus can be eaten fresh or stored for up to two weeks. Most people will find their citrus tree grows more fruit than the average household can use. Uneaten citrus can be processed into juice, marmalades, cordial, lemon butter, candied, or liqueurs, or shared with friends and neighbours. We share our limes with our neighbours, and they give us their excess lemons as our lemon tree is still immature.

| Citrus Fruit | Ideal Storage Temperature |

Storage Life |

|---|---|---|

| Orange (navel) | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Orange (Valencia) | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Lemon | 10-15°C (50-59°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Lime | 10-15°C (50-59°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Grapefruit | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Tangerine/Mandarin | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 1-2 weeks |

| Pomelo | 7-10°C (45-50°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Buddha’s hand | 10-15°C (50-59°F) | 1-2 weeks |

| Tangelo | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Yuzu | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Sudachi | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Finger Lime | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Kumquat | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

| Calamondin | 3-7°C (38-45°F) | 2-3 weeks |

Refrigeration can extend the shelf life of most citrus fruits, however, the best flavour is when the fruit is fresh. The storage life will depend on how ripe the fruit is when it is picked or purchased and how it is stored. Check your fruit regularly for any signs of spoilage.

Pests and diseases

Pest/Disease |

Symptoms |

Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| African citrus psyllid (Trioza erytrea) |

African citrus psyllid causes direct damage to the plant and can transmit the lethal Huanglongbing (yellow dragon disease, previously known as citrus greening disease). |

Contact your local government authority if you suspect your citrus has African citrus psyllid. |

| Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri) | Mottled leaves, stunted growth, yellowing, and leaf drop. |

Contact your local government authority if you suspect your citrus has Asian citrus psyllid |

| Citrus fruit borer (Citripestis sagittiferella) |

Holes and cracks in the fruit skin, fruit drop, and frass (insect feces) around the holes. |

Contact your local government authority if you suspect your citrus has citrus fruit borer |

| Citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella) | Curled or distorted leaves with silvery trails | Use a specific leafminer trap or pheromones |

| Citrus mealybug (Planococcus citri) | Chlorosis (yellowing) of the foliage, as well as leaf drop, stunted growth and reduced crop yields |

Maintain beneficial insects such as the mealybug ladybird (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri), lacewing larvae (Oligochrysa lutea) and parasitic wasp, Leptomastix dactylopii. Keep ant populations down as they feed on the sugar-rich honeydew and in return protect citrus mealybug. Mealybugs can be difficult to control with chemicals due to their resistance, waxy coating and their natural tendency to hide. |

| Citrus canker (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri) | Water-soaked, corky lesions on the underside of leaves, later becoming more raised and defined with a crater-like centre, encircled by a yellow halo. The disease manifests similarly on fruits and stems, presenting raised crater-like, corky lesions. Infected fruit may fall prematurely, and if lesions girdle the stem, branches may experience dieback. Left unchecked, can spread rapidly, significantly diminishing fruit yield and quality. |

Prune and destroy affected parts; copper sprays |

| Citrus tristeza virus (Citrus tristeza virus) |

CTV causes a disease known as quick decline, where infected trees rapidly wilt and die, often within a few years of showing initial symptoms. In other cases, CTV can cause stem pitting, where the bark of the tree develops elongated pits or grooves. Affected trees exhibit stunted growth, reduced fruit yield, and lower fruit quality. The fruit from infected trees may be smaller and display colour inversion, with the area closer to the stem remaining green while the end furthest from the stem becomes fully coloured. CTV can also cause seedling yellows in which young trees remain stunted and show yellowing of the leaves. |

No cure; use resistant rootstocks; remove infected trees |

| Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni) | Fruit damage, decreased crop yield, decreased fruit quality |

Monitoring (using fruit fly traps), sanitation (removing and disposing of infested or fallen fruit), the use of protein and insecticide baits, and in some cases, the use of male annihilation techniques or sterile insect technique (SIT). |

| Red scale (Aonidiella aurantii) | Yellowing and wilting of leaves, reduced vigour, and potential death of branches or entire trees if left unchecked. The feeding activity can also cause fruit to drop prematurely and result in a significant decrease in fruit quality, marked by yellowish, red, or brown spots on the rind where the scales were attached |

Parasitic wasps (Aphytis lignanensis and Aphytis melinus), ladybirds, chilocorus beetles and predatory mites. Parasitic wasps are commercially available. Sticky traps with synthetic red scale pheromones can be used to monitor for the presence of flying red scale. Movento is an insecticide produced by Bayer that is effective against red scale. |

| Root rot (Phytophthora spp.) | Brown or black roots become soft or rotted, in contrast to healthy roots which are firm and white. Above-groundsymptoms may initially be less evident but can include leaf chlorosis (yellowing), wilting, and overall tree decline. As the disease progresses, the canopy may thin and the tree may exhibit stunted growth. Fruit production can be significantly reduced, and the fruit itself may be smaller than normal. In severe cases, root rot can cause tree death. |

Good water management, fungicides if necessary. Can be hard to treat once the roots are damaged. |

| Yellow dragon disease (Liberibacter spp.) |

Yellowing of the leaves in an asymmetrical pattern, where one half or section of the leaf appears blotchy yellow while the other part remains green. Stunted growth, smaller, misshapen fruit that remains green at maturity, and has a bitter, off-flavour. Fruit and flower drop increase, leading to reduced yield. Additionally, the disease often leads to twig dieback, and in severe cases, it can result in the death of the entire tree. The symptoms may appear on a single branch at first and then spread to the entire tree. |

No known cure, prevention is key; remove and destroy affected trees |

Cold hardy varieties

- Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu): Satsuma mandarins are among the most cold hardy of citrus trees, withstanding temperatures as low as -7°C (20°F). They are known for their sweet, seedless fruit and generally ripen earlier than other mandarins.

- Kumquat (Fortunella spp.): Kumquats are very cold hardy, withstanding temperatures down to -7°C (20°F). They produce small, round or oblong fruit that can be eaten whole, including the skin, which is sweet and contrasts with the tart inner flesh.

- Yuzu (Citrus ichangensis x C. reticulata): Yuzu is a unique citrus used primarily for its aromatic zest and juice in Japanese and Korean cuisine. It can withstand temperatures down to -7°C (20°F). The fruit is typically not eaten fresh due to its large seeds and minimal flesh, but the zest and juice are highly prized.

- Trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata): While not a true citrus, trifoliate orange is often grouped with them because of its similar characteristics. It’s incredibly cold hardy, surviving temperatures down to -10 degrees Fahrenheit. The fruit is generally considered inedible due to its bitterness, but it is sometimes used to make marmalade. Trifoliate orange is often used as a rootstock for other citrus to impart its cold hardiness.

- Calamondin (Citrus x citrofortunella microcarpa): Calamondin is cold hardy down to -7°C (20°F). The fruit looks like a small tangerine and can be used as a tart substitute for lemons or limes.

- Improved Meyer lemon (Citrus x meyeri ‘Improved’): This is a hybrid citrus fruit native to China. It is a cross between a citron and a mandarin/pomelo hybrid distinct from both parents. The Improved Meyer lemon can handle temperatures down to around -7°C (20°F). Meyer fruit is sweeter and less acidic than common lemons.

Keep in mind that even these more cold hardy varieties can benefit from protection if extreme cold temperatures are forecasted. Wrapping the tree, using frost blankets, or employing outdoor lights can help prevent damage. Also, microclimates, such as those provided by south-facing walls, can help increase the cold hardiness of citrus trees in the landscape.

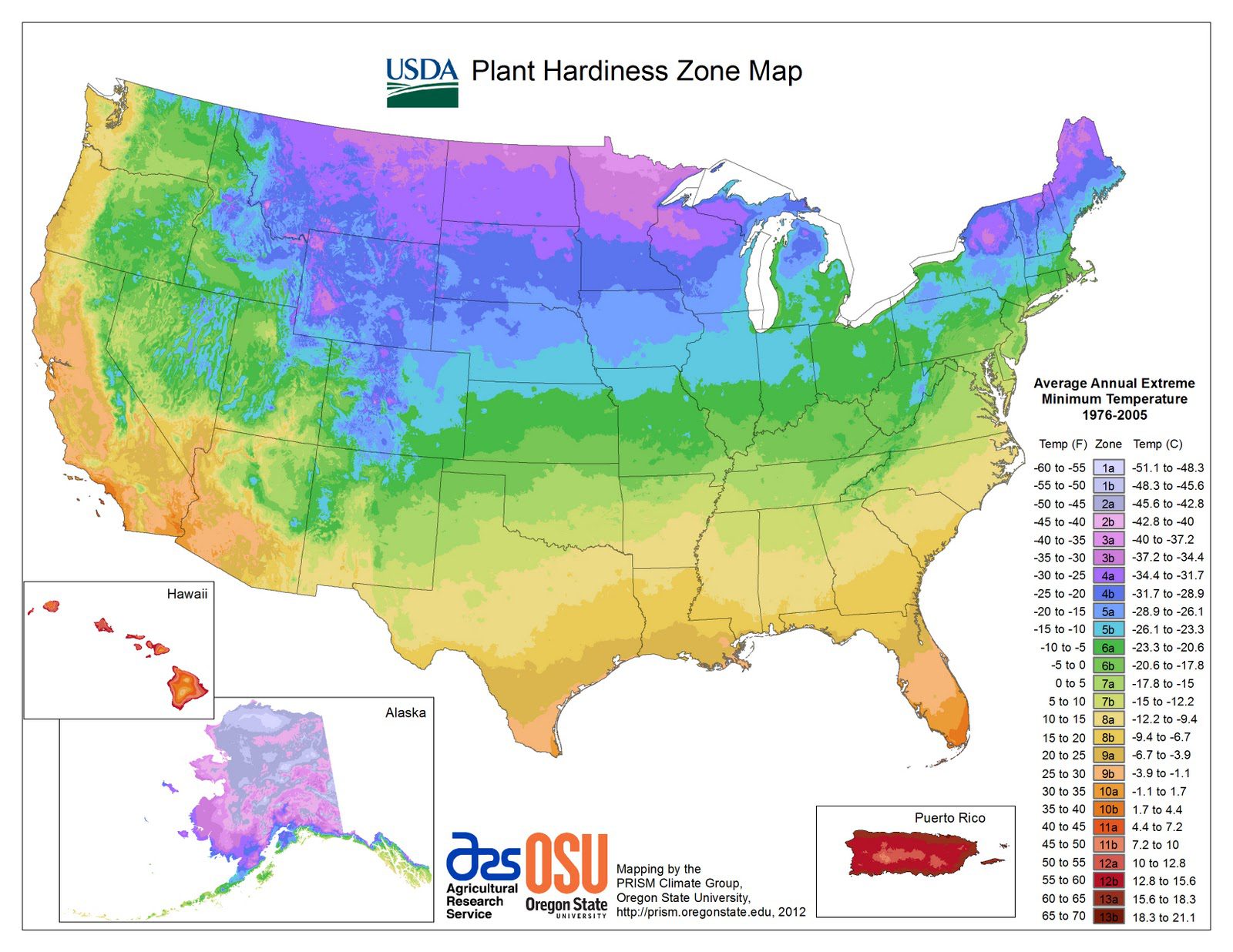

USDA hardiness zones of citrus varieties

The USDA hardiness zone is a resource developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to help growers determine which plants are most likely to thrive in a particular location. The map is divided into zones based on the average annual minimum winter temperature.

| Citrus fruit | Ideal climate |

|---|---|

| Orange (Sweet) | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-11 |

| Orange (Bitter/Seville) | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-11 |

| Grapefruit | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-10 |

| Lemon | Mediterranean, Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Lime | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Tangerine (Mandarin) | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Kumquat | Tropical, Subtropical, and Temperate, USDA zones 9-10 |

| Buddha’s hand | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-11 |

| Tangelo | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-11 |

| Yuzu | Cooler regions of Temperate, USDA zones 8-10 |

| Sudachi | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Finger Lime | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Calamondin | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 8-11 |

| Makrut (kaffir lime) | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 10-12 |

| Etrog (Citron) | Mediterranean, USDA zones 9-10 |

| Pomelo | Tropical and Subtropical, USDA zones 9-11 |

How long do citrus trees live?

Citrus lifespan can vary depending on the species, the conditions it is grown in and how well it is cared for. Under ideal conditions, many citrus trees can live for 40-50 years. Mother Orange Tree is a citrus that was purchased in 1856 and still bears fruit.

The lifespan of a citrus tree can vary significantly depending on the specific variety, the conditions it’s grown in, and how well it’s cared for. However, under optimal conditions, many citrus trees can live for over a century.

The productive lifespan of commercial citrus tends to be 20-30 years, after which time, yield declines and the tree is less economically viable.

With proper care, you can expand the longevity of your citrus and ensure maximum yield. Grow a variety that is suited to your climate, fertilise regularly, prune away dead or diseased branches and maintain shape to allow for good airflow, and routinely check for pests and diseases.

How long does it take citrus trees take to reach maturity?

Most citrus trees are approximately 1 metre tall when they are sold. It takes up to ten years for citrus to reach maturity. Removing fruit from young citrus trees allows the tree to direct its energy toward establishing a strong root system and growing in size, which can lead to better overall health and greater fruit production in the long term.

Which variety should I grow?

This depends on your local conditions and personal preferences. If you live in a cool area, look for frost-hardy varieties. I have been growing citrus trees for twenty years, and have learned a lot along the way. These days I am more mindful of what I am planting, why, and if I will actually use the fruit. Also, factor in how much fruit you will use or give away. For example, I have two lemon trees (admittedly, they are different varieties). A fully mature lemon tree can produce over 200 lemons a season. Can you use or give away 400 lemons? For most people, one tree per citrus type is enough.

Fruit availability

Another point to consider is the availability of citrus in supermarkets or fruit shops. Oranges are readily available year-round and are cheap. My preference is to grow citrus that is more expensive, or rare varieties such as sudachi or yuzu that aren’t available in Australian supermarkets.

We grow yuzu, sudachi, makrut lime, Australian finger lime, Buddha’s hand, pomelo and tangelo, which are rarely, if ever available to buy from supermarkets or fruit shops in Australia. In addition to the difficult-to-buy varieties, we also grow calamondin and kumquat as ornamentals, the fruit is a bonus. Common citrus varieties include lemon and lime, to make limoncello and limecello. There’s a 15-year-old dwarf mandarin I planted for my young daughter who loved mandarins. We don’t tend to use the fruit, so give it away. I would like to try mandarincello this year with some of the fruit. We also have two orange trees, which will likely be given away as we don’t eat the fruit.

Is it true that urinating on a citrus tree is good for it?

There is some truth to this as urine contains nitrogen, which is an essential macronutrient. However, the downside to this practice is that human urine also contains salt, which can build up in the soil over time and be harmful to plants. If it is done often enough, human urine can create an unpleasant odour around the tree. To be honest, I would prefer to use a balanced fertiliser than human urine.

What are the biggest and smallest types of citrus fruit?

The largest citrus fruit is the Pomelo (Citrus maxima). This fruit can reach of up to 30 cm (nearly 12 inches) in diameter and can weigh as much as 2 kg (about 4.4 pounds) or even more.

The smallest citrus fruit is generally accepted to be the kumquat (Fortunella species). The fruit is usually about the size of a large olive.

Julia is a writer and landscape consultant from Wollongong with a love of horticulture. She had been an avid gardener for over 30 years, collects rare variegated plants and is a home orchardist. Julia is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge of plant propagation and plant toxicology. Whether it’s giving advice on landscape projects or sharing tips on growing, Julia enjoys helping people make their gardens flourish.